Green architecture – Portola Valley Town Center

The Town of Portola Valley and the design team developed a new master plan through an open and participatory process, a series of public workshops that focused on the Town Center program, site opportunities and constraints, and sustainable design goals on this 11-acre parcel. A new Library, Town Hall, and Community Hall frame a new town green. Extensive use of salvaged materials, reliance on daylighting, natural ventilation, and low-tech building systems reduced the ecological footprint of the new buildings and gave it LEED Platinum Certification.

The Town of Portola Valley and the design team developed a new master plan through an open and participatory process, a series of public workshops that focused on the Town Center program, site opportunities and constraints, and sustainable design goals on this 11-acre parcel. A new Library, Town Hall, and Community Hall frame a new town green. Extensive use of salvaged materials, reliance on daylighting, natural ventilation, and low-tech building systems reduced the ecological footprint of the new buildings and gave it LEED Platinum Certification.

The activists who founded the town of Portola Valley, Calif., in 1964 were determined to protect its scenic hillsides south of San Francisco from large-scale residential development. That same philosophy came into play 40 years later, when the town decided to replace a remaining school with a multi-use town center. The top priorities: preserving open space, restoring natural habitat, and connecting to the landscape.

The new Portola Valley Town Center occupies an 11-acre site beside a meadow and walnut grove. But its three main buildings (library, town hall, and community hall) are placed away from the location of the old school, which was discovered to have been straddling the San Andreas Fault. By tucking the new complex in a corner of the site, the architects made space for a new baseball field, tennis courts, and a 300-foot-long stretch of restored creek that had been diverted into a culvert.

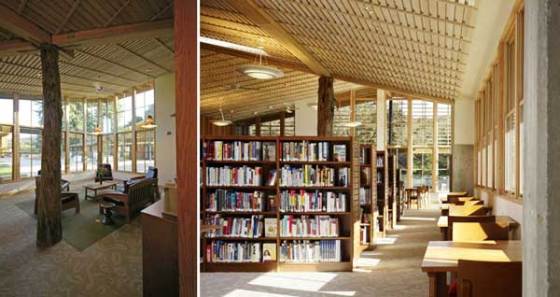

Designed in collaboration of two firms, Siegel & Strain Architects and Goring & Straja Architects, the civic center benefits from the enlightened views of town staff and highly involved citizens, who raised most of the money for the complex privately. The buildings huddle around a paved plaza and public lawn, where events such as an annual barbecue festival are held. Wide gabled roofs lend a familiarity to the buildings, whose deep sheltering porches and sunscreens of reclaimed Alaskan yellow cedar shade generous windows. Reclaimed vertical redwood siding relates the buildings to two towering redwood groves on the site.

Sustainability was a vital issue to the town, which consistently raised the bar as the project advanced. “Most of our projects get watered down as they go along,” says architect Larry Strain. “This one got greener and greener.” Rather than simply demolishing the old school, they disassembled it to salvage materials. Douglas fir planks were re-milled into wall paneling and ceiling slats for the new buildings. Concrete and asphalt were ground and reused as base rock for paths and service roads. In total, some 90 percent of the material from the deconstructed buildings was saved from landfills.

The comfortably scaled interiors reveal other eco-friendly gestures. Flooring in the community hall’s large meeting room, for example, was milled from local eucalyptus trees. Alder trees cut down to make way for the new ball field now wrap distinctive columns inside the buildings. And high-slag concrete—used in foundations, floor slabs, and library alcoves—lowered the project’s carbon footprint by 125 tons.

Building systems serve the sustainable agenda too. Passive design strategies include natural ventilation, daylighting, thermal mass, and exterior shading. In the most heavily used buildings, radiant-floor heating and nighttime cooling systems keep energy use to a minimum.

Three arrays of roof-mounted photovoltaic panels, coupled with the efficient design, result in 53 percent less energy use than required by code. The arrays of roof-mounted photovoltaic panels generate 76 kW of power on site. The architects specified SunPower 210 panels with an efficiency rating of 16.9 percent, one of the highest available ratings. They also selected the panels for their uniform black appearance, which complements the design of the buildings.

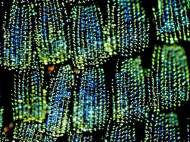

The architects designed slatted ceilings to improve acoustics in important interiors, including the library reading room, town hall lobby, emergency operations center, and multipurpose room in the community hall. Working with 9Wood, a Springfield, Ore., manufacturer of suspended wood ceilings, the architects salvaged 2×6 roof decking from the old school and remilled it into 1×3 slats with a resawn finish to absorb a stain. The wood was pickled with a white stain to increase reflectivity and improve day-lighting.

Large double-hung windows and awning windows in the clerestories allow for natural ventilation. The architects selected aluminum-clad windows from Loewen because of the manufacturer’s promise of extended life and reduced maintenance. In addition, Loewen makes the windows with FSC-certified wood, which was an important consideration. The windows are dual-glazed with Cardinal LoE3 -366 coated glass, which combines good light transmittance and thermal performance.

Large wall areas in the two community hall classrooms— used frequently for children’s education—are covered in Forbo Marmoleum Bulletin Board. This low-VOC, biodegradable material is made from linseed oil, cork, resin binders, and dry pigments mounted on natural jute backing. The cork qualifies as a rapidly renewable resource.

Strain says the goal from the start had been to make the buildings green without seeking LEED certification. Midway through the process, the town decided to go for LEED Platinum. “We finally realized that the project would be easier to get built as a green project with LEED behind it—that the contractors understood what that meant,” Strain says. “It’s a way of implementing green.”

Leave your response!